By Pushpa Kumari

October 5, 2018

Whether macroeconomy is up or down and asset markets hawkish or dovish, surprisingly inflation rate has done very well during the last two to three decades in the developed economies. It raises so many questions. Has price level, a signal of macro-level economic activity, lost its telling power because of monetary policy engineering? How are relative prices so well behaved that these never upset the macro price level? How could relative prices, especially of consumer goods (as the consumer price index is generally used in the inflation targeting), remain so low that inflation rate almost always remains within its target? How the targeted inflation rate has been achieved successfully within the same macroeconomy in which economic growth has been stagnant, domestic manufacturing has lost its ground, asset economy has been boiling, and financial vulnerabilities have been piling up? These questions lead the present commentary to examine the modus operandi of the inflation targeting as an integral part of the management of the macroeconomy in the developed economies.

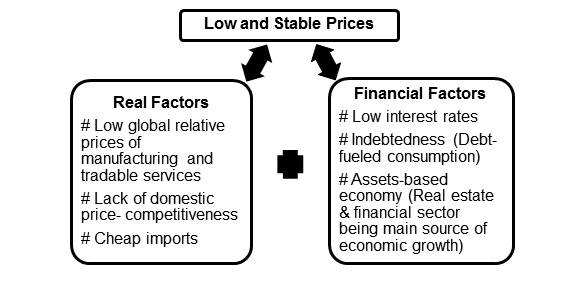

Graph 1: How Price Stability has Co-existed with Weakening Real Economy and Increasing Financial Vulnerabilities in the Western Economies

Graph 1 shows the mechanism how the price stability has been achieved alongside the weakening real economy and vulnerable financial sector. In fact, this graph depicts how poorly the western world has managed their economies in an era of global competition. The shield of low and stable prices has released the pressure from politicians and policy-makers to reform and restructure their economies. Thus, it triggers the discussion that these economies should re-examine the monetary policy regime of inflation targeting and review the entire maneuvering how the inflation targets are achieved.

It has been two-sided dynamics, global and domestic – global factors could enable domestic inflation rate to remain low, and domestic factors kept running the economy and building the financial vulnerabilities at the same time. At the root is the lack of domestic price-competitiveness of manufacturing goods and tradable services vis-a-vis imported ones. In an open economy, when there are readily available imports at cheaper prices who would like to pay for domestic higher priced goods and services. The market would play its role, and obviously imports would be preferred at the cost of domestic products and thus the related industries.

There is a potential for active (rather, proactive) role for the policy intervention here. However, policy-makers can actually play either an active or passive role in this kind of circumstance of global competition. Either they can increase domestic competitiveness with the help of conducive policy-choices and let domestic industries compete with the global imports. Or they can leave economies onto the mercy of market mechanism and let imports flood and fill the markets and consequently kill the domestic industries. Instead of first, a hard route, and making reforms to create competitiveness in their economies, unfortunately, western economies, the so-called warriors of globalization, preferred the second, i.e., an easy route, and let imports take over. Balance of payments reflects the impact of those bad policy-choices in terms of current account deficits.

Not to forget, some developed countries, e.g., Germany and Japan, have successfully met the global competition by augmenting price-competitiveness in their economies; Germany by controlling wages and Japan by profit margins. Also, the East Asian success story of the active role of government in furthering competitiveness in their economies has already been proven.

Perhaps, this is the reason that even too low rate of interest for too long could not help the domestic industry to pick up in the capitalist countries. Instead, it has fuelled the asset markets in these economies. Businesses compare the rates of return across the various alternatives for their investment. When they find speculative assets more lucrative than the highly competitive goods & services’ industries with low global relative prices and low returns, they would make rational choices and prefer assets’ investments over real economy investments. Investing in speculative assets and earning higher returns has been as rational a choice on the part of businesses, as buying lower priced goods and services on the part of consumers.

To complete the jigsaw puzzle, financial deregulation and liberalization have done their part by facilitating the abundant supply of capital. The stable and low inflation rates – alongside deindustrialization-led general deflationary fears (even amidst the asset bubbles), and liberalized financial markets – have allowed the rates of interest to remain low for an overstretched period of time.

Therefore, lack of (manufacturing and tradable services’) competitiveness in global competition made productive investment avenues limited, diverting the investments towards speculative assets on the one hand; financial liberalization facilitated the cheaper finance in abundance to fuel the asset markets on the other. On the other spectrum, anemic economic growth in the western industrial economies made it almost essential to depend on the borrowed funds for the households to maintain their consumption levels. The low interest rate regime has given extra incentives to the households to build-up their debts. The financial sector enjoyed its profit bonanza from the economies based on the debts and asset bubbles, in the process making the financial system susceptible to instabilities.

How far has inflation targeting been responsible in the game of economic stagnation (or even decline) and financial vulnerabilities? It has been responsible to the extend:

- it has released the pressure from the politicians and policy-makers to take actions to increase competitiveness in the domestic economy;

- it has let manufacturing die in the face of global competition, and has led to the decline of alternative productive investment avenues for the businesses;

- it has led to import-dependency and created imbalances (e.g., current account deficits) in the economy; and

- it has allowed financial vulnerabilities built-up by letting the interest rate remain too low for too long, and to create asset bubbles and household indebtedness.

It is how a need to keep the inflation rate within target has been making the western economies almost junk economies with import dependence and financial addiction. Central Banks and policy-makers should stop self-applause now on their targeted-inflation achievements. They should better critically review their myopic-focused monetary policy regime of the inflation-targeting, considering its direct and indirect consequences on the macroeconomy. It is high time to re-examine the inflation targeting in light of struggling economies of the developed world before these turn into ghost economies!